The One Calibration Question That Changes How You Use AI

A Practical Framework for Conscious AI Engagement

Key Points

Your brain experiences borrowed capability as your own. You can’t distinguish between “I did this with AI” and “I can do this”.

How you engage with AI determines whether it amplifies or erodes your capacity, not whether you use it at all.

One calibration question guides conscious AI use: How much of ME does this task require: my thinking, my review, or just completion?

Hello friends,

Have you finished a project with AI assistance and felt proud of the output but slightly hollow about your role in creating it? Or used AI to speed through work, then struggled to explain your own thinking when someone asked follow-up questions?

That dissonance between productivity and ownership is a signal worth listening to.

Today, I want to give you something practical to resolve it: a framework for using AI in ways that amplify your thinking rather than replace it. I distilled months of research on how AI can amplify or erode our thinking, and 1.5 years of my daily use, to one core question that will guide your conscious AI use.

But first, you need to understand why you can’t trust how you feel about your AI use.

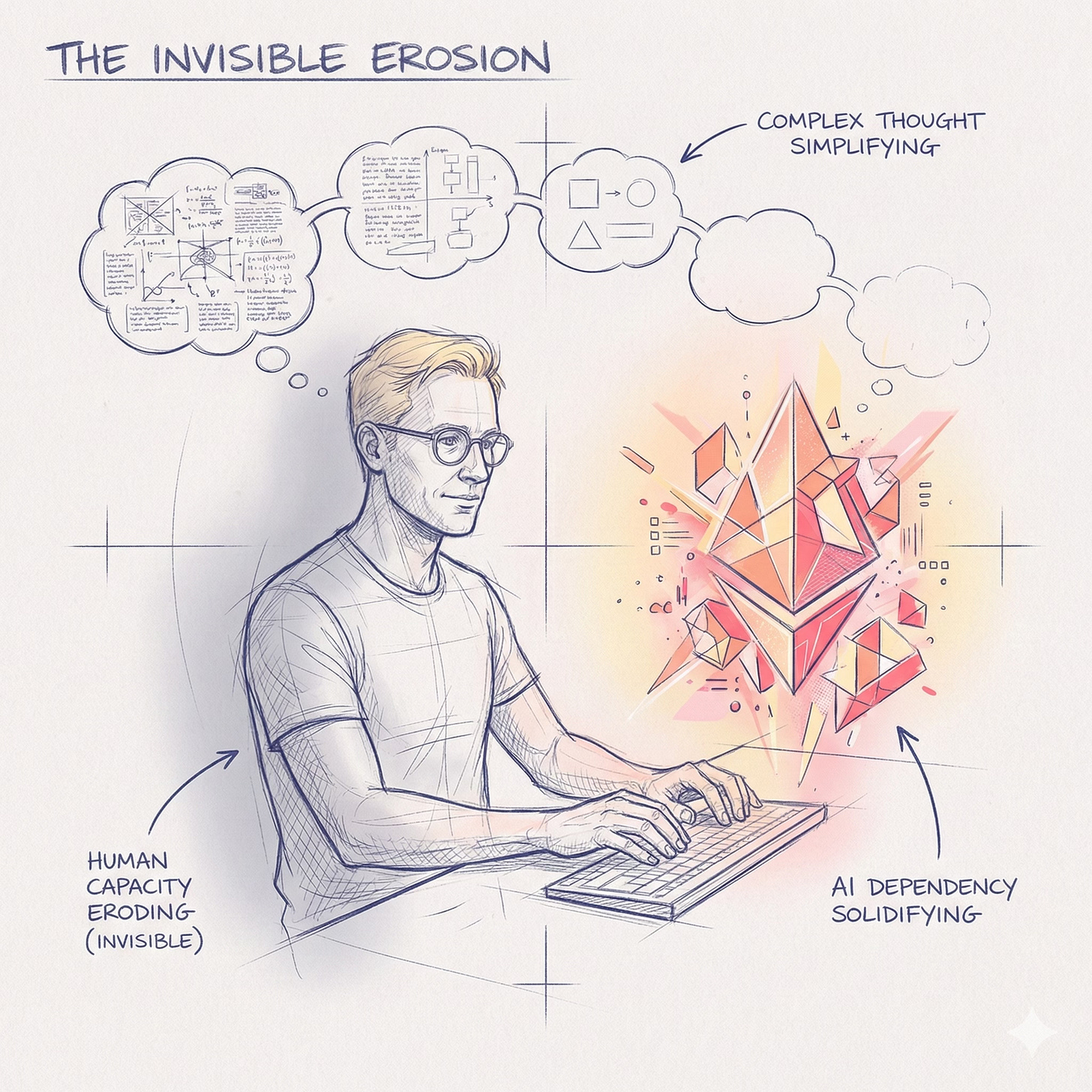

Your brain can’t tell the difference

Every interaction with AI creates tension: productive struggle (which builds capacity) versus AI assistance (which feels smooth and productive). Most people drift toward assistance without noticing because thinking is hard and AI is effortless.

The danger is invisible while it’s happening.

Your brain experiences borrowed capability as your own. You complete tasks with AI help, which triggers the same satisfaction signals as genuine competence. Your nervous system can’t distinguish between “I did this with AI” and “I can do this”.

Have you used AI to complete a complex task, then found yourself unable to do similar work when AI wasn’t available? That’s not incompetence. That’s your brain’s inability to separate AI’s capability from yours during the original task.

Have you read an AI summary of research and felt like you understood it, then struggled to explain the concepts to a colleague? Your brain mistakes AI’s fluent output for your own comprehension.

Have you felt accomplished after completing more tasks faster with AI, without noticing your capacity to do quality independent work was shrinking? Productivity feels like growth, but volume doesn’t mean your capacity is growing.

This isn’t a personal failing. Our brains prefer cognitive ease over effort. Automation bias (trusting AI too readily) makes us favor what AI proposes. Cognitive offloading (letting AI think for us) makes us delegate thinking when tools are available. AI amplifies this naturally – it’s fluent, confident, and persuasive even when wrong. The combination makes AI use feel smooth and productive, while solo work feels harder by comparison.

The typical cycle: You use AI to speed through work. Something feels off, hollow, not quite yours. You promise to use less AI next time. Time pressure hits. You reach for AI again. The cycle repeats. You wake up when you realize doing the work without AI has become difficult or impossible.

You think you’re maintaining capability. But reasoning, judgment, and originality are quietly eroding.

So how do you escape this cycle? The answer isn’t avoiding AI. It’s changing how you engage with it.

How engagement mode determines outcomes

AI doesn’t inherently amplify or erode your capacity. How you engage with it makes the difference.

The same person using the same AI on the same task can produce opposite outcomes. You can use AI to think better or to avoid thinking. The choice happens in how you structure the interaction.

Amplifying engagement means AI makes you think better. It extends your capability, builds understanding, preserves or develops capacity. Amplifying patterns:

You think before using AI (don’t go straight to AI)

You evaluate critically with your expertise and intuition

You transform AI output significantly (not just minor edits)

You use AI to challenge and extend your thinking (not replace it)

You generate foundation or first draft yourself first

These patterns work because YOUR brain does the cognitive work: forming ideas, making judgments, creating connections. AI scaffolds and challenges, but doesn’t replace your thinking.

Eroding engagement bypasses your thinking, prevents learning, and degrades judgment. Eroding patterns:

You go straight to AI without engaging your thinking first

You accept AI output verbatim or with minimal changes

You trust AI without critical evaluation

You use AI to avoid thinking or struggle

You let AI generate foundation

These patterns erode capacity because AI does the cognitive work while you merely evaluate output. Your brain is in consumption mode, not creation mode.

Knowing these patterns isn’t enough. When you’re reaching for AI, you need a simple way to choose the right engagement.

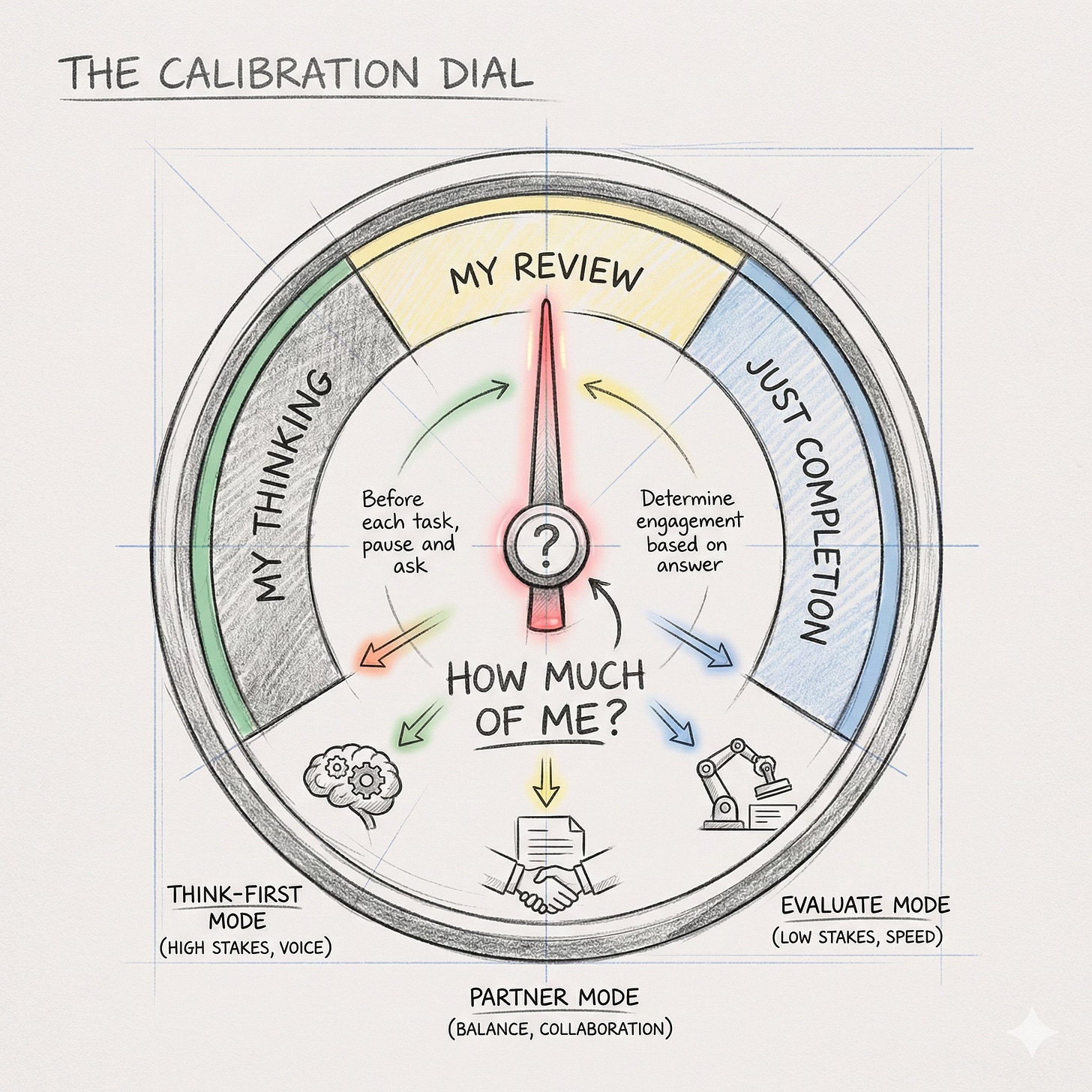

The calibration question

Before each task, ask yourself one question:

How much of ME does this require: my thinking, my review, or just completion?

This question does two things. First, it interrupts the automatic reach for AI. Second, it forces you to articulate what actually needs your brain versus what AI can handle.

Your answer determines how you engage with AI, not whether you use it, but how. It maps directly to who does the cognitive work:

My thinking → Think-First Mode

My review → Partner Mode

Just completion → Evaluate Mode

Think-First Mode

You do substantial solo work first: outline, analysis, rough draft. Then use AI to challenge, extend, or polish what YOU created. When AI contributes, you transform it significantly, making it yours.

When to use this:

High stakes work where quality matters most

Your unique voice or perspective is the value

You’re building expertise in this domain

Partner Mode

You seed the direction, AI expands, you evaluate critically. This is a back-and-forth collaboration where you’re rejecting or rewriting 40-60% of what AI suggests. You’re not accepting output, you’re in active dialogue.

When to use this:

You have enough expertise to evaluate quality

Balance between speed and maintaining capacity

The task doesn’t require your unique voice

Evaluate Mode

AI generates a draft, you catch errors and improve the output. You add context AI lacks, verify accuracy, and ensure it meets requirements. You’re confident you can spot problems because you’re already strong in this area.

When to use this:

Low stakes work where you’re already an expert

Time pressure requires speed

Your expertise makes the evaluation reliable

I don’t choose to do hard thinking solely to preserve my capacity. I do it because quality, authenticity, and voice matter.

I bring more of myself when:

The work must be top-notch, reflecting my best thinking

My unique perspective or experience is the value

The output should sound like me, not a generic AI

I want to own the result as genuinely mine

Watch how this works in practice

Let me show you how I use all three modes within a single task of writing this newsletter.

Step 1: Solo Ideation (Think-First Mode)

I close all AI tools and brain dump thoughts in a note. This struggle builds the cognitive foundation everything else rests on.

Step 2: Research to inform my thinking (Partner Mode)

I use AI to find relevant sources, then I read and synthesize them myself. The reading feeds my brain with ideas.

Step 3: Developing thinking (Partner Mode)

I bring my raw thinking to AI and ask it to shape it with Socratic dialog (question-driven discussion). It forces me to look at the problem from different perspectives, find connections I didn’t know existed, challenge my thinking, and form my thinking more quickly.

Step 4: Structure article (Partner Mode)

I ask AI for article structure and flow options, then I evaluate and choose based on the story I want to convey.

Step 5: Solo Writing (Think-First Mode)

With AI closed, I draft on my own. I sit with the discomfort of not knowing what to say. That’s where my voice emerges.

Step 6: Critical feedback (Partner Mode)

I ask AI to review the draft critically. Then I decide which feedback makes sense and make the edits.

Step 7: Technical polish (Evaluate Mode)

AI acts as an editor for grammar, style, and clarity improvements.

Notice the alternation: Step 1 is Think-First. Steps 2-4 are Partner Mode. Step 5 returns to Think-First. Steps 6-7 shift to Partner and Evaluate. I move through all three modes within one task.

Try This

This week: Before each AI interaction, pause and ask:

Does this need my thinking, my review, or just completion?

Choose your mode based on that answer, then follow that mode’s pattern, especially the alternation rhythm. Observe whether the work felt different when you consciously chose how to engage.

When you’re not sure which mode to choose, default to Think-First. Better to do extra solo work than to delegate thinking you needed to do yourself. You can bring AI in mid-task, but you can’t reclaim cognitive engagement after outsourcing it.

Success looks like this: Your cursor is in ChatGPT’s or Claude’s text box. You’ve typed a prompt asking AI to draft something. You pause. You realize you’re about to delegate thinking you actually need to do yourself. You close the window and open your notebook instead.

That pause is success. That’s you maintaining the capacity that makes you valuable. Experiment, refine your calibration over time, and develop intuition for which mode serves which goal and workflow.

A Final Thought

While working on this material, I experienced how AI amplifies not my thinking but my counterproductive behavior, and makes it harder to notice and break the self-defeating cycle.

I have serious impostor syndrome that makes me procrastinate on publishing work.

I have a number of ways to avoid the dreaded moment of publication. Do just another round of research with a slightly different angle. Ensure my writing aligns perfectly with current research. Endlessly perfect my concepts. Just empty busyness to feel productive while never delivering.

In December, after my LinkedIn posts got half a million views, I became obsessed with getting this framework right.

I went through three complete attempts to model the dynamics of AI use with layers of dependencies and nuance. Each time, I’d bounce ideas off AI for hours, refining, restructuring, exploring edge cases.

AI made it so easy to keep going. The analysis felt productive. I was working hard, thinking deeply, making progress.

Except I wasn’t. The prompting illusion felt identical to being productive and making progress.

I was stuck in analysis paralysis. I was heading toward burnout.

AI eliminated the friction that would have forced me to stop sooner. Without that friction, I could iterate endlessly, never shipping anything.

If you find yourself iterating endlessly, optimizing perpetually, or analyzing when you should be doing, pause.

AI amplifies what it encounters. It amplified my productive thinking when I used it correctly. But it also amplified my procrastination, making endless iteration feel like diligent work instead of avoidance.

The friction that would have forced me to stop sooner (exhaustion, frustration, running out of options) never came. AI kept offering new angles to explore. I had to create my own stopping point: deciding this was done enough and shipping it.

– Paweł

P.S. I’m interested in bringing this approach to organizations adopting AI responsibly. If your team wants to adopt AI without eroding the cognitive capacity that makes them valuable, let’s talk.

Sources & Further Reading:

Research study (2024). Practice With Less AI Makes Perfect. Passalacqua et al. found partial automation leads to 23% better skill development than full automation, workers who stayed in the decision loop preserved both skills and motivation.

Research study (2023). The Metacognitive Demands of Generative AI. Study showing AI creates metacognitive challenges where users struggle to monitor their own thinking when AI does the cognitive work, leading to overconfidence in borrowed capability.

Research Policy (2024). Robots, Meaning, and Self-Determination. Nikolova et al. studied automation’s impact across 20 European countries, finding it consistently reduces autonomy and competence satisfaction, core psychological needs for meaningful work.

Extremely well articulated, I think there's also something to be added here on the thinking first before using AI (understanding goals and outcomes as well).

In my mind, this is not only limited to understanding the how (My Thinking, My Review, My Completion) but also extends to having the subject matter expertise to know exactly what your goals are and understand the problem well enough to articulate it with no confusion. I see this as a flexible time period, either in the span of a few minutes, or can be the result of weeks, months, or years of thinking critically about the topic/ goal/ task at hand, etc...

Your three approaches are spot on, though, exactly how I see myself using AI every day and a mental framework I use to course correct when I'm engaging ineffectively.